You are here

Companies as systems

After working in the non-profit sector for the better part of a decade, I am distinctly aware of the many challenges it is facing. Funding, governance, human resources, politics – these issues, and many more – have daily and long-term implications for how organizations can continue to operate.

However, in the for-profit sector, a significant movement is occurring that addresses social inequalities. What started as a small signal of Corporate Social Responsibility for many large companies is now a full business model rethinking. Benefit Corporation is a legal for-profit business framework being implemented all around the world and at significant scale. This framework outlines, for legal purposes, how businesses can implement a balance of people, planet and profit objectives into the very DNA of a company. This has significant implications for how both the for-profit and non-profit sectors can and will operate moving forward.

Arising from this legal framework is a certification called B-Corp, which assesses a company’s implementation of the benefit corporation framework. The assessment covers approximately 40 versions, based on company size and industry vertical, with each assessment version containing about 200 questions, 175 of which are common to each assessment version. Approximately 1,229 companies have achieved certification in 38 countries across 121 industries (as of February 2015). While not significant in scale, it does represent a growing movement.

To achieve certification, companies must score a minimum of 80 out of 200 on the assessment. Assessment questions attempt to discover the relationships and interactions companies have with a variety of their internal and external stakeholders, to understand how a company has embedded the treatment of people and planet in its business objectives. Some companies may score high on environmental practices and low on employee and community engagement, or visa versa, but still achieve certification.

A For-Profit Company as a System

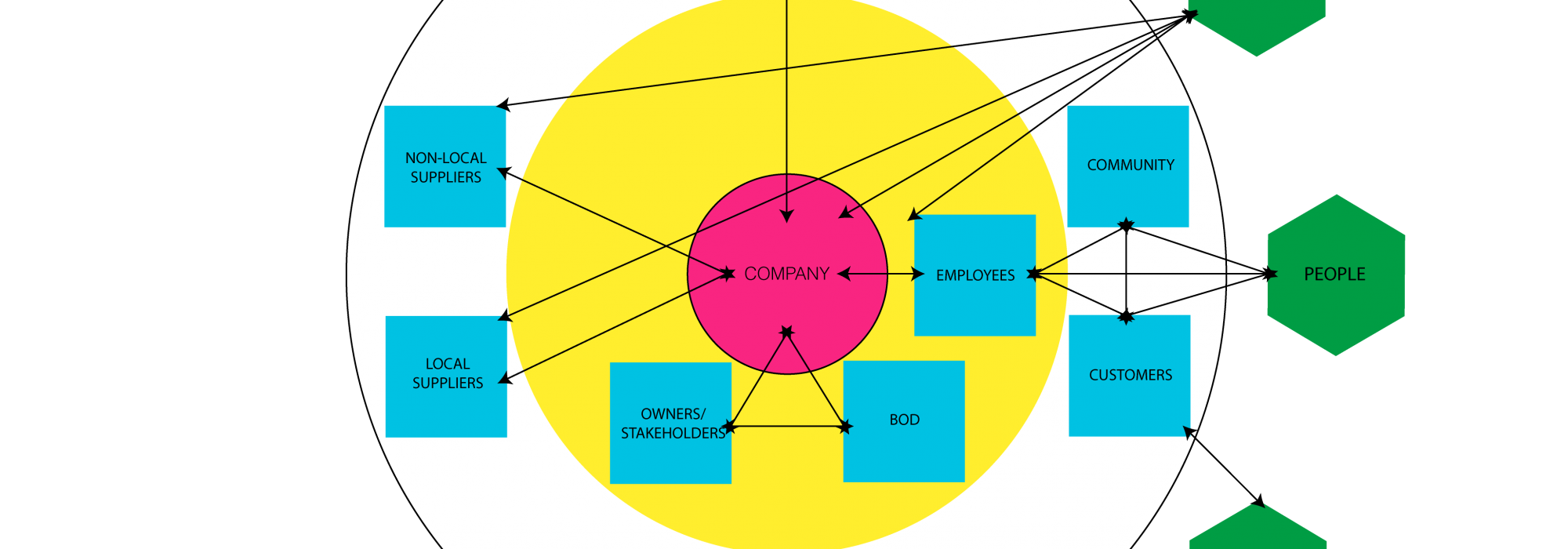

When mapping out a for-profit company, its system diagram looks extremely linear. Inputs and resources are acquired from suppliers, transformed into outputs by the company, and sold through employees to customers. Each of these interactions is defined by its intent to create or increase profit.

In order to grow profits companies have four options:

1. Lower the cost of inputs coming from suppliers

2. Use inputs more efficiently in the production of outputs

3. Sell outputs at a higher margin

4. Sell outputs to more customers.

In each case, the focus on profit makes a company blind to an indeterminate number of factors within these system interactions that could otherwise affect its resiliency. As a metaphor, this is like a community focusing exclusively on its ability to handle potential earthquakes, leaving it vulnerable to subsequent tsunamis and disease, or a different disaster altogether. While profit and profit margin are good indicators of current success, they are less helpful as long-term predictors of a company’s health. Why then do for-profit companies tend to focus primarily, if not exclusively, on profit?

The Benefit of B-Corps

While B-Corp is a certification and not a legal business framework, in order to achieve certification, the assessment has been designed to ensure a company has thought about further dimensions within its stakeholder interactions. Where for-profit companies have a focused vision to understand a narrow dimension, profit, B-Corps are using their peripheral vision to think in multiple dimensions, people, planet and profit. These dimensions represent a level of foresight about risk factors beyond profit that could have immediate and long-term implications for a company’s resilience.

If a company thinks of itself as part of a broader system with dynamic interactions, it can begin to understand how supporting balanced system dynamics can be mutually beneficial for all the stakeholders within that system, including itself. For example, if a company works with its suppliers to access inputs that are affordable to the company, but also produces enough profit for the supplier to keep its doors open, then the company can have a greater level of comfort/certainty that it will continue to have access to those inputs into the future. Additionally, companies can also work with suppliers that understand and protect the planet and its sustainability. If the supplier is creating its inputs in a sustainable manner, then there is less risk that the inputs it produces for the company will be affected by resource constraints or environmental degradation, amongst other things, over time.

Going through the certification process, then, isn’t just about joining a movement of benefit corporations, but a lens through which a company can view and subsequently improve its system dynamics.

Thinking Beyond B-Corp for Business Resilience

While B-Corp is advancing knowledge about the role of companies in society, it became evident in the process of mapping its system model that there was a significant blind spot in the periphery. Understanding a company’s competitors and building into its DNA how it will handle these relationships could be vitally important. This is one area where for-profits could learn something from non-profits. Coalitions are an interesting dynamic at play in the non-profit sector, where competitors may agree to pursue common goals for the benefit of a particular issue or, as is increasingly common, within a particular geographical area. By coalescing around a particular system objective, each stakeholder in the system is able to glean benefit.

If for-profits added this view into their thinking, it would reinforce the system as a whole. For example, where companies are in direct competition, this increasingly means a race to the bottom where they produce a better product at a lower price – in other words at a lower profit. Eventually, this is a lose-lose scenario for companies, because even if they end up winning market share, they risk losing money. While there are certain legal ramifications for attempts by groups of companies to fix prices at a certain level, the principle remains a useful one. Can companies that compete with one another also coalesce around a mutually beneficial environmental or social objective? I would guess there are some interesting examples of this model being implemented, but they were outside this research.

Challenges in Mapping B-Corps

The primary challenge in mapping a B-Corp certification based company was in understanding the role values play. It is often argued that Benefit Corporations are based on values, but this perception prevents objectivity when evaluating what B-Corp certification meant to a system mapping of the for-profit business models. While in one sense the certification process is a series of values judgments, it is also about business decisions if a company is prepared to think and plan beyond the immediate future. From this objective, bird’s-eye level, the system map takes on a perceptive 360-degree shape that is an apt visual.

There are also questions about the utility of this model for companies with a long-term history in profit-focused business. There are examples of companies that have made the transition, even some that are publicly traded companies. However, these are far from the norm, and it is more common to see young companies started with the Benefit Corporation model in mind, making implementation of the certification more of a formality then a process. For the B-Corp Certification’s future growth, it will be important to be framed as a resilience framework, with feet in both profit protection and people-planet support. In doing so, it should open the doors to a much larger, and significantly more influential, market.

- Systems

Error message

- Warning: "continue" targeting switch is equivalent to "break". Did you mean to use "continue 2"? in include_once() (line 1439 of /home/coreynorman/companybe.ca/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- Deprecated function: Optional parameter $conditions declared before required parameter $data is implicitly treated as a required parameter in include_once() (line 1439 of /home/coreynorman/companybe.ca/includes/bootstrap.inc).

- Deprecated function: Optional parameter $item declared before required parameter $complete_form is implicitly treated as a required parameter in include_once() (line 1439 of /home/coreynorman/companybe.ca/includes/bootstrap.inc).

Comments